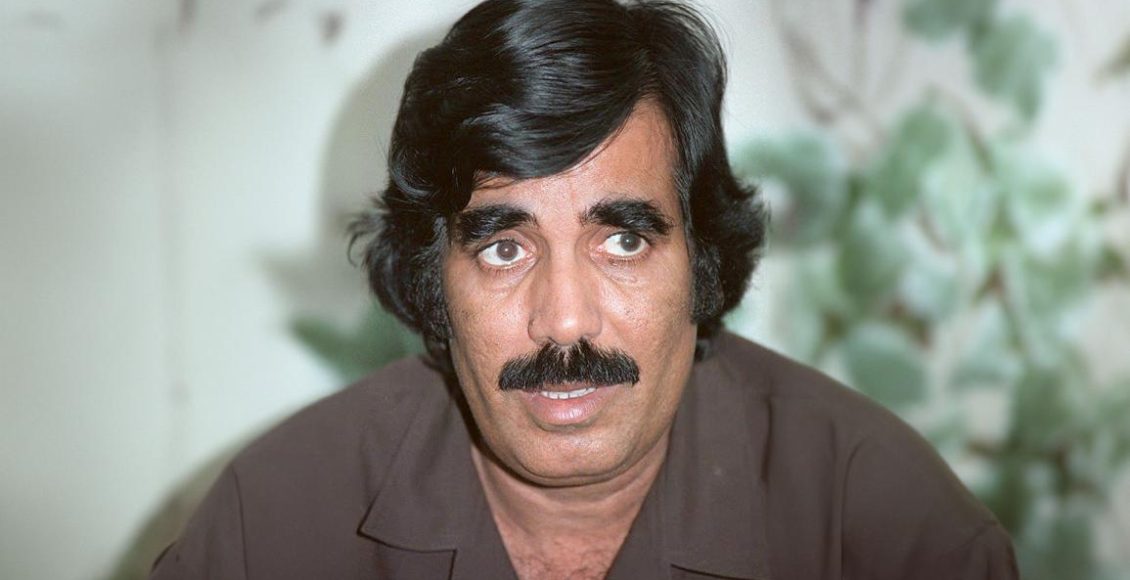

SANAA, Oct. 30 (YPA) – British documents have revealed that London refused to grant former Vice President Ali Salem al-Beidh a visa to enter its territory after the 1994 civil war, fearing he would lead the opposition against the Sanaa regime at that time.

A newly released series of secret diplomatic cables from the British government confirmed its refusal to host Ali Salem al-Beidh, who applied for a British visa a few months after the end of the 1994 civil war, due to concerns that he would engage in opposition political activities from British soil.

Researcher Hamed al-Kinani wrote in the Independent Arabia newspaper on Thursday that, according to the documents, Britain feared the diplomatic repercussions of granting al-Beidh a visa, despite a previous approval in August 1994 following pressure from Muscat and Riyadh on London.

The British government later changed its stance as relations with Yemen improved. The British Foreign Office deemed al-Beidh’s presence in London not to be in the public interest, thus ending his attempts to enter the country.

According to cables from the British Embassy in Oman, which date back to 1994 and 1995, the British government considered the political and diplomatic ramifications of a visa application submitted by the former Yemeni Vice President, Ali Salem al-Beidh, to enter the United Kingdom in late 1994. Al-Beidh was residing in Oman as a political refugee following the 1994 civil war.

Al-Beidh signed the Yemeni unity agreement with Ali Abdullah Saleh, the former president of Yemen, in Aden and declared Yemen on May 22, 1990. They jointly raised the flag of unity and shared power until May 1994, when war broke out and lasted until July of the same year.

The newly released documents revealed a rejection decision issued by the British Home Secretary on December 22, 1994, regarding al-Beidh’s application for a visa to enter the United Kingdom as an investor. The British decision came as a result of prior consultations between the British Home Office and the Foreign Office, which had submitted a memorandum on December 2nd of the same year regarding the request. After studying the matter and considering the Foreign Office’s advice, the Home Secretary concluded that preventing al-Baidh from entering British territory was in the public interest and would preserve the United Kingdom’s relations with the Republic of Yemen.

Despite the then-Home Secretary’s acknowledgment that al-Baidh’s political background was controversial, the primary justification for the decision was not that background, but rather diplomatic considerations related to London’s relationship with Sanaa.

Accordingly, the visa application had been rejected. It was noted that al-Baidh had no right to appeal the decision through the usual immigration channels. However, the document indicated that al-Baidh could, theoretically, resort to judicial review to challenge the decision, especially considering that the British government had agreed in August of the same year to grant him a short-term visitor visa, following pressure from the Foreign Office.

With the British Home Secretary’s decision, the British government effectively ended Ali al-Baidh’s attempt to enter the United Kingdom at a time when Yemeni-British relations were extremely sensitive diplomatically following the unification of Yemen and the ensuing civil war.

According to the documents, on January 13, the British Foreign Secretary sent a confidential cable, numbered 12, to the British Embassy in Sanaa, with copies to the UK Embassy in Muscat and Riyadh. The cable, titled “Al-Baidh,” indicated that the British Home Office had formally informed Al-Baidh’s lawyer that day of the decision to bar him from entering London. This decision was contradicted previous advice, as outlined in paragraph four of the 1994 TUR report, which had apparently recommended a more flexible approach to his request.

The Foreign and Home Offices agreed on a unified press line to address potential media inquiries about the decision. The line stated that the Home Secretary had decided to exclude Ali Salem Al-Baidh from the UK because his presence was not in the national interest.

The cable was concluded with a directive from the Foreign Secretary to British embassies in the region, instructing them to inform him if they required any additional materials or instructions for dealing with the relevant Yemeni or Omani authorities regarding the case.

On January 26, 1995, R.W. Gibson of the Middle East Department at the British Foreign Office prepared a memorandum to special advisors concerning the visa application submitted by Yemeni politician Ali Salem al-Beidh, the former vice president and one of the most prominent leaders of South Yemen.

R.W. Gibson referred to the Home Secretary’s remarks in his memorandum were dated on December 22, 1994, which indicated that the British government might have to justify its refusal, especially since London had initially expressed its willingness in August of the same year to grant al-Beidh a visa for medical treatment after strong pressure from the Foreign Office.

He explained that there had been valid reasons for the Foreign Office’s change of position since then, and that London’s agreement in August to grant al-Beidh a visa for medical treatment was the result of pressure from the governments of Oman and Saudi Arabia. Muscat had been openly calling for him to be allowed entry into the United Kingdom, and Riyadh supported the same position. London believed that refusing the visa application could strain its relations with both capitals. However, the British government was not enthusiastic about this approach and refused to allow his family to accompany him. Ultimately, al-Baidh did not make the trip to Britain.

After al-Baidh submitted a new application to enter the United Kingdom as an investor, the British position had changed drastically.

By then, the political and regional circumstances had been shifted. Oman was no longer pressuring for his entry and even seemed receptive to the idea of him settling on its territory. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia had begun to mend its relations with the Yemeni regime in Sanaa and had lost its previous interest in him.

Amid these shifts, British-Yemeni relations were gradually improving. London felt that allowing al-Baidh entry at this stage would not be politically advantageous and might even provoke objections from the Yemeni government, hindering the rapprochement without offering any tangible benefit to its relations with Muscat or Riyadh.

AA